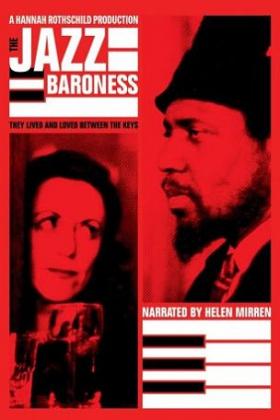

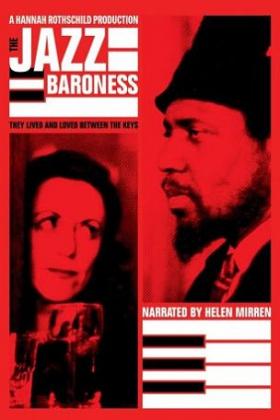

review of The Jazz Baronness, clip from T.S. Monk, Helen Mirren reads Nina Rothschild’s letters

This film tells the story of the life of Pannonica Rothschild de Koneigswarter, an actual Baroness and heir of the Rothschild family fortune, her love of Thelonious Monk, and her unceasing support of jazz as an essential art form.

The history of jazz has been one of second-class status as an art form. Musicians may have gigs all the time, they may even become famous. But the sad truth is that almost none ever becomes financially secure, let alone well off. This was especially true in the bebop era. It is perhaps even rarer that anyone from the upper crust of society would take on the role of being a patron of this art. Pannonica or Nica as her friends called her, was that. She used her position and wealth to help jazz artists and was loved in return. There are over 20 compositions written about her from her personal friends such as Monk, Horace Silver, Kenny Drew, Tommy Flanagan and Art Blakey to name but a few.

It is almost like a fairy-tale, that a Jewish woman from one of the wealthiest families in Europe would decide to leave that world behind when she discovered the music of an African-American man from rural North Carolina via New York City. Their backgrounds and their social classes make their meeting seem almost unimaginable.

Nica learned about jazz from her brother Victor who was Churchill’s personal courier to Roosevelt and who had studied piano with Teddy Wilson. Her connection to Monk began as a stopover in NYC on her way back to Mexico when Teddy Wilson told her that she had to hear the then-new recording of “Round Midnight.” She listened to it 20 times in a row, missed her plane and never made it back to Mexico but instead was pulled under the spell of that music and, once she met Monk, two years later in Paris, was hardly ever apart from 1952 until his death in 1982.

By all accounts, they were never lovers but it was clear that they loved each other and were best friends. Nica had a close relationship with Monk’s wife and children and when he became too sick to perform and tour Monk lived in her house for the last 10 years of his life with the blessing of his wife Nellie and children.

Their lives had some parallels. Both had limited options, hers as an independent woman coming of age in the 1930s. As a Rothschild, her career was expected to be finding a husband which she did when she married Baron Jules de Koneigswarter, banker and later a French diplomat. For Monk, music was one of the few options available to an African-American growing up under Jim Crow laws and a segregated America.The film addresses a family history with mental illness, Nica’s sister and father and Monk’s father, as well as his own well-documented struggles. This too may have drawn Nica closer to Monk.

The film touches on Nica’s life before jazz when, living in France under the specter of Nazism, she smuggled her children out of France and then smuggled herself back to join her husband fighting with the Free French armies in Africa where she drove ambulances, decoded messages and perhaps began her life as a freedom fighter.

Juxtaposed was Monk’s life and his struggles to gain recognition and hold onto his cabaret card that would allow him to work in New York clubs. Nica grasped Monk’s genius a good 10 years before the critics and before many musicians, and she dedicated her life and her resources to helping make his life easier as well as for countless other musicians, paying their rent, visiting them in the hospital, serving as a booking agent. She may have also bought them drugs but there seems to be no evidence that drugs were a part of her lifestyle. She went so far as to buy more than one Steinway so they’d have a decent piano to play in the nightclub.

Her apartment on 5th Avenue was a kind of jazz salon where after hours musicians could unwind, eat and drink hang out and of course have jam sessions. Needless to say, the management and many of her neighbors were uncomfortable with the inclusion of black jazz men into their Upper East Side life. After Charlie Parker died in her apartment she was forced out of the Stanhope Hotel and then moved to the Bolivar Hotel on Central Park West where Monk wrote many great tunes at her Steinway. Nica held off criticisms of her lifestyle as long as she could until she was forced to move out and finally took up residence in a house in New Jersey, just across the bridge with a spectacular view of the Hudson river and the New York skyline. Named the “Cat House” because all the musicians hung out there as well as her hundreds of cats, it became a sanctuary for musicians. Barry Harris continues to live there, years after her death in 1988.

Over the years Nica did everything she could to support and protect Monk including taking the rap for $10 marijuana possession that could have carried 3 years in prison followed by immediate deportation. Although she did spend some time in jail, a technicality allowed her to avoid that fate.

In this film their intertwining stories are told through the remembrances of a host of jazz musicians, critics, managers, as well as members of Nica’s family, and rare letters of Nica’s as read by Helen Mirren. It is a story far too rich in detail for us to capture all the remarkable dimensions but anyone who is a lover of jazz and social history will really enjoy seeking this film out.

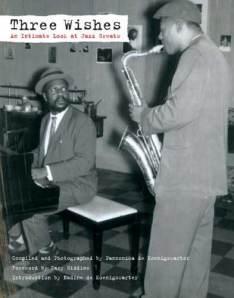

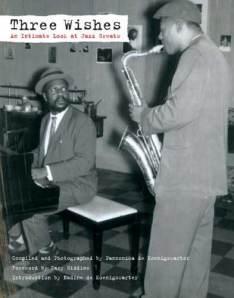

For those who want more we suggest that you also look at Nica’s own book Three Wishes: An Intimate Look at Jazz Greats, (compiled by her granddaughter) including her most candid photography and answers to her playful question “what are your three wishes?” As the Jazz Baroness on the music scene for over three decades, more than likely she granted a number of wishes all on her own.

To see more, visit

KUVO .

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))