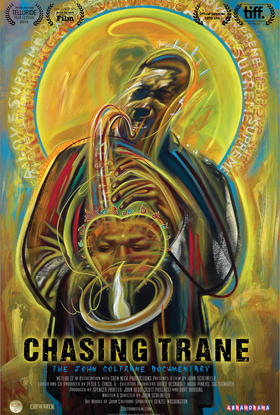

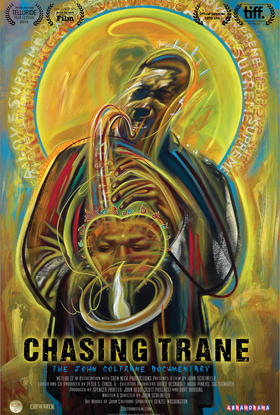

John Coltrane is a name many people have heard. To jazz fans, Coltrane is a name they associate with one of the great icons in 20th century music. And simply ‘Trane’ is whom other musicians and deep fans evoke to speak, sometimes in hushed tones, of a singular artist who elevated the saxophone into the realm of the profound and the spiritual. John Scheinfeld’s documentary has something in it for each of those people. Although Trane only lived to age 40, he had a gigantic influence in the jazz world. In talking about the multiple periods of Pablo Picasso’s career, President Bill Clinton notes that Coltrane did everything Picasso did in 50 fewer years.

The film begins in 1957 with Coltrane newly married and a step-father, working at the top of his field as a member of the first classic Miles Davis Quintet, but also wrestling with a terrible heroin and alcohol addiction. The film uses talking heads, including biographers Ashley Kahn, Ben Ratliff, and Lewis Porter, childhood friends Jimmy Health and Benny Golson, as well as his children, and others. Drawn from interviews and liner notes, Coltrane’s own words are read by Denzel Washington. Like all good documentaries this one features loads of rare photographs and even rarer live performances. Where “Chasing Trane” is a cut above the rest is that not only are there great performances but his music underscores the entire film, playing underneath dialogue and during visual montages. It is used to great effect to further deepen the periods in his story and the reflections of others. Classic numbers such as “Giant Steps,” “My Favorite Things” and “A Love Supreme” all get special attention.

The people interviewed provide reverential feelings and insightful observations not just about Trane as a man and musician, but just as importantly, they provide poetic evidence of his larger-than-life spirit, how he used his music to preach for universal love and peace. One particularly poignant example comes first from Dr. Cornel West who defines black music as “the black response to being terrorized and traumatized. We gonna spread some soothing sweetness against the backdrop of a dark catastrophe.” That point is beautifully illuminated with the story behind his composition “Alabama,” a requiem for the four little girls who were killed in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Trane’s melody was inspired by the cadence of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s eulogy. The piece carries the pain and love not simply from that terrible event but Coltrane used it to look back in history and forward into the future.

Trane practiced constantly and mastered the technical side of playing, proving he was equally astounding at interpreting ballads and standards. Later, with Miles’ guidance, he became endlessly inventive within the structures of hard bop and modal playing, but stepped away from the tried and true went his own way, into a far more spiritual approach to composing and playing. Although they are now iconic and emulated by any number of current players, the sounds that he created on his tenor and soprano saxes had never been heard before. And in his album “A Love Supreme,” Trane created an extraordinary suite that, for the first time, used jazz as vehicle to share with the audience the relationship between the artist and his God. It is every bit as sacred as works by J.S. Bach and deeply touched people. At a point in his career where he was at the peak of popularity, with a hit record—“My Favorite Things”—and public recognition, Coltrane dismantled his classic quartet in 1965 to follow his own vision and quest for a universality in sound. This lost him fans and critics as people struggled (and many gave up) to understand this new music seemingly uncoupled from all the familiar signposts of jazz—swing, chords, melody. His music took on both a more meditative tone as well as a far more dense and urgent sound. Some dismissed it as shrieking but Trane saw it as cleansing and a continuation of his desire to use his music to be uplifting. That debate continues to this day.

In one of the most remarkable segments, the film remembers his trip to Japan, what amounted then to his final tour in 1966. A grueling schedule of 16 shows in 17 days included a trip to Nagasaki. His tour guide said that the band had departed from the train but Trane remained sitting playing his flute and when asked, said that he was trying to tune into the place and the people. He asked to be taken to the atomic blast site and offered a prayer in front of the memorial and during the show played as his second number his composition “Peace On Earth” that deeply touched the audience, still recovering from that terrible event. Within a year, he was dead at age 40 from liver cancer. There were little indications of any illness prior to the diagnosis and he had lived a clean life for much of his 30s.

Perhaps no other figure in jazz inspires the level of spiritual reverence as John Coltrane. The film walks us through his life and his development as an artist and reveals how broad his influence is with people as diverse as John Densmore (the Doors), Bill Clinton, and rapper Common. It is difficult to capture in words the profound impact of John Coltrane’s music. I am reminded of the Taoist saying about the finger pointing at the moon. The analogy describes the relationship between spiritual teaching and reality as that of a finger pointing at the moon. When trying to help another to see the moon, one might point a finger toward the sky. The intent is to have the other follow the finger to see the moon directly. Trane pointed the way towards a broader and deeper connection between music and the universality of being human. Some got lost looking for the well-known indicators, the melodies, the rhythm, did it swing, and may have missed (or dismissed) the bigger picture he was after. Others are still searching.

“Chasing Trane” is an excellent film with something for everyone. It is a fine introduction to those wanting to learn who he was. For the fan, there are plenty of examples of the wonderful music he made, and if you are a disciple, there are also his reaches into outer space and his quest for revealing his humanity, in all its forms, through his playing. While not everything in his life is covered (how could it?) or given the attention some might desire, the film is a long time coming as it is the first truly full picture of this great artist and well worth our attention.

Copyright 2019 KUVO . To see more, visit

KUVO .

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))