Jaco: Wild, Untamed, Complicated | Jazz on Film Review

KUVO host Matthew Goldwasser PhD reviews the documentary “Jaco.”

In the world of bass guitar there is everyone before Jaco Pastorius and there is everyone after him. In the history of 20th century music only a handful of musicians stand out as truly revolutionizing what was possible from their instruments. Charlie Parker, Jimi Hendrix, and Jaco Pastorius are in that elite group. Interestingly, none of them lived beyond their early 30s and all three are instantly recognizable by one name only—Bird, Jimi, Jaco.

The early innovators on upright bass include Jimmy Blanton, Oscar Pettiford and Charles Mingus and Cuban musician Israel ‘Cachao’ Lopez. While the electric bass was invented in 1930s, it wasn’t until Monk Montgomery played it in Lionel Hampton’s orchestra in the early 50s that it began to be an accepted alternative to the upright. In the 1960’s and early 70s new innovators from R& B and soul such as Motown’s James Jamerson with his one finger, (‘the hook’ )style of soloing, Jerry Jemmott, and Larry Graham and Louis Johnson–pioneers of the ‘slap technique– began to expand the range of sound the electric bass could offer. The Rolling Stones’ Bill Wyman is largely acknowledged as the first to play a fretless bass (circa 1961). Jaco Pastorius, the self-proclaimed “world’s greatest bass player” took all their styles into the stratosphere with his utterly original combination of deep groove, astounding harmonics, a symphony of colors and textures, and a profoundly innovative way of soloing and providing accompaniment.

To state that his technique was jaw-dropping is to point out the obvious. In the documentary “Jaco,” (2015, directed by Paul Marchand – who hails from Fort Collins, Colo., and Stephen Kijak) Joni Mitchell impressionistically contrasted every other bass player she worked with and Jaco as the difference between ‘picket fence’ playing and ‘putting big dark polka dots along the bottom of the music.’ As Herbie Hancock described him upon first hearing him, he had his own sound, the ultimate goal of any musician. Perhaps as befitting genius, Jaco was also a complicated person. Possessing an enormous ego and zest for life, consumed with the music he heard in his head, he was also a sometimes fragile and tortured soul whose own chemical and psychological imbalances contributed to a tragic, violent, and premature end.

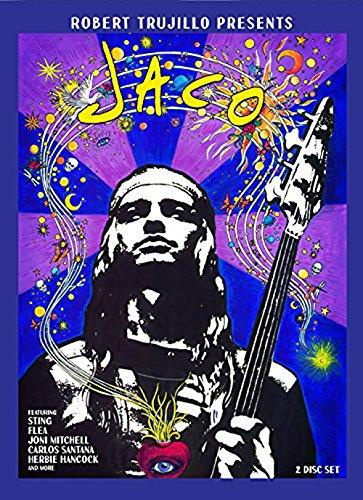

The documentary “Jaco” is labor of love. Co-produced by Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo, it features commentary across the jazz, pop, rock, and funk worlds. The film shows the deep regard and impact Jaco had on musicians both contemporaries and who came after him. Structurally, the film tells his story chronologically but without the use of a narrator. Instead, we are treated to wonderful archival photographs and home movies from his boyhood in South Florida, the early bands he played and toured with as well as performances befitting his superstar status with the seminal fusion band Weather Report, Joni Mitchell, and his own solo projects. From free jazz player Paul Bley to rocker Ian Hunter, from Ira Sullivan to Tony Williams, Jaco’s musical sensibilities and tastes ran across a huge diversity. If it was hip, Jaco was into it. Along the way we hear from his family and friends, those who worked with him, and we hear both about his genius and his demise. Writer and friend Bill Milkowski wrote the definitive biography in 1995 (Jaco-The extraordinary and tragic life of “the world’s greatest bass player”) and an expanded edition came out in 2006. Milkowski and many of his interviewees appear in the film.

The film takes an even-handed approach. One musician after another expounds on his immense talents and the charismatic personality that burst onto the scene in the late 1970s at a time when the genre of jazz fusion was musically adventurous and commercially lucrative. Many of these same musicians and friends were also candid about the alcohol and drug use (cocaine in particular) that was commonplace then. Although originally a straight arrow who was only into playing music and sports, the film chronicles Jaco’s falling deeper into the trappings of fame and notoriety, drugs and alcohol, and that combustible alchemy between his huge ego, his unbounded creativity, his manic-depression and his increasing inability to handle everything at once. It didn’t help that his own solo efforts, while lauded by musicans and critics, were not commercial successes nor did they catapult him into the upper echelons of being a crossover superstar. Over time he began to alienate almost everyone who was ever in his corner.

Diagnosed as bi-polar and hospitalized briefly his mental condition deteriorated, no doubt exacerbated by his fierce denial of reality. Friends and family tried but couldn’t help him. He had several disastrous performances that embarrassed his band mates and further isolated him from getting future gigs. He was reduced to living on the streets of New York and in the parks in Florida. His companions were other street people, a world away from the international fame and glamour he enjoyed just a few years earlier as he toured the world with Weather Report. In the end a savage beating by a south Florida club bouncer who had no idea who he was left him in a coma and he died a few days later weeks shy of his 36th birthday.

Jaco Pastorius was in constant and creative motion. His was a wild, untamed spirit. In his short lifetime he was a comet, a musical Aurora Borealis across the sky. Music poured out of him like a fountain. Underneath his fun-loving, clown side, even at its worst, was a deep spiritualty that drew others into a state of being in the moment, musically and in life. He revolutionized what was possible on the electric bass, his mastery of harmonics, counterpoint, deep groove, blazing speed, and tender soul. Less celebrated but no less significant were his skills at composition and arrangements. He started out on drums and could not at first read music but probably could have mastered any instrument he wished. Instead he made his bass sound like an electric guitar, a French horn, a saxophone, congas, a human voice and a symphony orchestra, sometimes all in the same tune. One after another musician in the film reach for superlatives. Bootsy Collins said “Where do you go after Jaco? There’s not much more soul and feeling and vibe that’s original.” Everyone in the film has a Jaco story, something amazing about him (even while the credits roll). Watch it and be amazed for yourself.

[Note: the DVD contains 100 minutes of additional outtakes, anecdotes, stories as well as footage from the Hollywood Bowl’s Jaco’s World tribute concert from earlier in 2015.]

See more Jazz on Film reviews here.

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!