Mingus Ahem! New biography reviewed

In this new biography, Better Git It in Your Soul, author Krin Gabbard expresses gratitude for the Mingus biographers who supplied him with much source material—Brian Priestly (1982), Gene Santoro (2000), and Sue Graham Mingus (2002). And thank you to Charles Mingus, the author of maybe the most sensational jazz memoir ever, Beneath the Underdog: His World as Composed by Mingus (1971). Adding to the instrumental music and his novelistic memoir, Charles also wrote poetry—not well-known, but equally stirring. Gabbard scoured audiotapes in the Library of Congress collection for the following Mingus ode: “I myself have died a million deaths in a row/I myself have died more than you could ever know/Killed at the white man’s stake/And beaten and burned. Must I read your books and your philosophies? Must I follow your pathway or your gold? Can I now become a man of my own true self? Can I not grow inside and fear nothing on my own?”

Author Gabbard is in awe of Mingus complexity—the subject defies characterization. In his memoir, Mingus had described himself as three: a gentle man, an assertive demander, and a patient receptor. The Mingus identities can be found in his book characters and music titles (e. g. “All the Things You Could Be by Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother”). He has said that without success as a musician he could have been a pimp, using his many women friends to pay the bills. Sexual bravado pervades his memoir. In his life, violence is present in addition to emotional pain. He self-commits to Bellevue; Gabbard argues that Mingus suffered from bipolar disorder. The books and poetry reflect his frustrating search for self-understanding and racial justice.

Mingus cut a broad path through many different music phases and genres. Raised in Watts, a black neighborhood in Los Angeles, Gabbard gives us an expanded discussion of the Rodia sculpture, Watts Towers, implying the piece positioned only one to two blocks from the Mingus family home instilled an artistic interpretation to Charles’ early impressions. The colorful character sketches start here—Buddy Collette, a jazz band leader and only one year older, tells the young classically trained cellist Mingus he “was not likely to break into the highly segregated world of classical music,” and should switch to the bass and play in his band. To make it real, Collette introduced him to Lloyd Reese, a mentor to many West Coast jazz greats, for music instruction, and later bassist Red Callender, who taught Mingus the bowing and finger position techniques that produced “the sound on his (Callender) early recordings with (Lester) Young and (Nat King) Cole.” While in high school, Mingus, Collette, and teenager Chico Hamilton were in a band playing in clubs between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Gabbard pays well-documented tribute to long-standing, but suffering, Mingus sidemen: drummer Dannie Richmond, reedist Eric Dolphy, and trombonist Jimmy Knepper. With other jazz greats the storied-connections are less direct–this group includes Coleman Hawkins and Howard McGee. When Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were in Los Angeles, Bird was recording with McGee. We are to infer that Mingus probably played with Parker at this time because he was recording with McGee. Continuing the music chronology, “Five years after he was discovered by (Barney) Bigard, and two years after he first played with Coleman Hawkins, Mingus joined up with another old master of the big band era, Lionel Hampton.” Both Hawkins and Hampton are profiled at length. Mingus left Hampton in hopes of finding success as a band leader. But first, there was an interesting association with the racially diverse and musically innovative Red Norvo Trio: vibraphonist Norvo, bassist Mingus and guitarist Tal Farlow. Norvo and Mingus knew how to play without a pianist and drummer. Their style was groundbreaking at a time when many felt “boppers were dragging down jazz as a popular music.” But, was this yet another music style for the critics to hack at? Gabbard describes the Trio work by drawing comparisons with the Miles Davis music of the period that was later collected in Birth of the Cool. “Whether they (the Trio) are playing familiar ballads such as ‘September in the Rain’ and ‘Where or When’ or bop tunes like ‘Budo’ and ‘Good Bait,’ the excitement of bop and the openness of cool are always present.” Cool jazz and bebop would become part of “straight ahead” jazz.

In the late 50’s, Mingus was forerunning the free jazz movement of Ornette Coleman and others. Mingus always encouraged his bandmates to be expressive (while reminding them who was in charge). However, Gabbard writes, “Mingus had been slow to respond to the challenges of bebop, and he was suspicious of the ‘free jazz’ of Coleman.” He provides this Mingus quote, “Kenny Dorham and I tried to get Ornette to play ‘All the Things You Are’ straight, and he couldn’t do it.” Mingus later gave Coleman his just due, for in a Downbeat “blindfold test” Mingus says this about Coleman’s playing, “It’s like not having anything to do with what’s around you, and being right in your own world.” Maybe the ultimate compliment delivered an “improv” artist.

Film buffs may enjoy a full chapter of reviews in the book epilogue, “Mingus in the Movies.” The films with a Mingus acting part include John Cassavetes’ Shadows and the British film All Night Long. Mingus songs were used to raise the emotional intensity in Jerry Maguire (“Haitian Fight Song”), The Whole Nine Yards (“Moanin’”), Mo’ Better Blues (“Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”), U Turn (“II B. S.”) and in the opening sequence of Absolute Beginners (“Boogie Stop Shuffle” and “Better Git It in Your Soul”). If the movie isn’t so hot, you can dig the music.

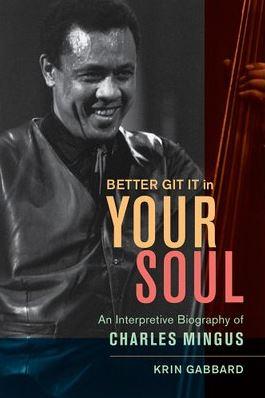

Gabbard, Krin. Better Git It in Your Soul: An Interpretive Biography of Charles Mingus. University of California Press: Oakland, CA. 2016.

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!